Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Otosclerosis - From Merck Manual

In otosclerosis, the new bone traps and restricts the movement of the stapes, causing conductive hearing loss (see Hearing Loss). Otosclerosis also may cause a sensorineural hearing loss, particularly when the foci of otosclerotic bone are adjacent to the scala media. Half of all cases are inherited. The measles virus plays an inciting role in patients with a genetic predisposition for otosclerosis.

Although about 10% of white adults have some otosclerosis (compared with 1% of blacks), only about 10% of affected people develop conductive hearing loss. Hearing loss from otosclerosis may manifest as early as age 7 or 8, but most cases do not become evident until the late teen or early adult years, when slowly progressive, asymmetric hearing loss is diagnosed. Fixation of the stapes may progress rapidly during pregnancy.

A hearing aid may restore hearing. Alternatively, microsurgery to remove some or all of the stapes and to replace it with a prosthesis may be beneficial.

Loss of low frequency sound first

Presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, is the cumulative effect of aging on hearing. Also known as presbyacusis, it is defined as a progressive bilateral symmetrical age-related sensorineural hearing loss. The hearing loss is most marked at higher frequencies.

Middle Ear Infection - From Merck Manual

Middle ear infections are extremely common between the ages of 3 months and 3 years and often accompany the common cold. Young children are susceptible to middle ear infections for several reasons. The eustachian tube, which balances pressure within the ear, connects the middle ear with the nasal passages (see Middle and Inner Ear Disorders:Barotrauma). In older children and adults, the tube is more vertical, wider, and fairly rigid, and secretions that pass into it from the nasal passages drain easily. But in younger children, the eustachian tube is more horizontal, narrower, and less rigid. The tube is more likely to become obstructed by secretions and to collapse, trapping those secretions in or close to the middle ear and impairing middle ear ventilation. Any viruses or bacteria in the secretions then multiply, causing infection. Viruses and bacteria can move back up the short eustachian tube of infants, causing middle ear infections.

Besides differences in anatomy of the ear, infants at about the age of 6 months become more susceptible to infection because they lose protection from their mother's antibodies, which they received through the placenta before birth. Breastfeeding appears to partially protect children from ear infections because the mother's antibodies are contained in breast milk. Children also become more sociable around this time and may develop viral infections by touching other children and objects and putting their fingers in their mouth and nose; these infections may in turn lead to middle ear infections. Exposure to cigarette smoke further increases the risk for middle ear infections, as does the use of a pacifier, both of which may impair the function of the eustachian tube and affect middle ear ventilation. Attendance at childcare centers increases the risk of exposure to the common cold and hence to otitis media.

Middle ear infections can resolve relatively quickly (acute), or they can recur or persist over a long time (chronic).

Acute Middle Ear Infection

Acute middle ear infection (also called acute otitis media (see Middle and Inner Ear Disorders: Otitis Media (Acute)) is most often caused by the same viruses that cause the common cold. Acute infection may also be caused by bacteria found in the mouth and nose, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. An infection initially caused by a virus sometimes leads to a bacterial infection.

Infants with acute middle ear infections have fever, crying or irritability that sometimes cannot be explained, and disturbances in sleep. They may also have a runny nose, cough, vomiting, and diarrhea. Infants and children who cannot fully communicate may pull at their ears. Older children are usually able to tell parents that their ear hurts or that they cannot hear well.

Commonly, fluid may accumulate behind the eardrum and persist after the acute infection has resolved (serous otitis media). Rarely, acute middle ear infection leads to more serious complications. Rupture of the eardrum can cause drainage of blood or fluid from the ear. Infection of the bone surrounding the ear (mastoiditis) can cause pain; infection of the inner ear (labyrinthitis) can cause dizziness and deafness; and infection of the tissues surrounding the brain (meningitis) or brain abscesses (collections of pus) can cause seizures and other neurologic problems. Recurring infections can promote growth of skinlike tissue through the eardrum (cholesteatoma). Cholesteatoma can damage the bones of the middle ear and cause hearing loss.

Doctors diagnose acute middle ear infections by looking for bulging and redness of the eardrum with an otoscope. They may need to clean wax from the ear first so they can see more clearly. Doctors may use a rubber bulb and tube attached to the otoscope to squeeze air into the ear to see if the eardrum moves. If the eardrum does not move or moves only slightly, then infection may be present.

Acetaminophen or ibuprofen is effective for fever and pain. Doctors used to give antibiotics to all children with acute middle ear infections. However, they now realize that many acute middle ear infections improve without antibiotics. Thus, many doctors use antibiotics (such as amoxicillin with or without clavulanate, or trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole ) only when the child does not improve after a brief period of time or if there are signs that the infection is not getting better.

Chronic Middle Ear Infection

Chronic middle ear infection occurs as a result of repeated acute infection or when recurring infections damage the eardrum or lead to formation of a cholesteatoma, which in turn promotes more infection. Chronic ear infections are more likely among children who are exposed to cigarette smoke, use pacifiers, and attend group day care centers. For children with chronic ear infections, doctors may recommend daily antibiotics for several months. If infection persists or recurs despite the use of antibiotics, or if chronic infections have led to eardrum damage or formation of cholesteatoma, doctors may recommend ventilating (tympanostomy) tubes, eardrum repair, or surgical removal of the cholesteatoma.

Serous otitis media - from Merck Manual

Serous otitis media often occurs after acute otitis media. The fluid that has accumulated behind the eardrum during the acute infection remains after the infection resolves. Serous otitis media may also occur without preceding infection, and may be due to gastroesophageal reflux disease or a blockage of the eustachian tube by infection or enlarged adenoids. Serous otitis media is extremely common in children between the ages of 3 months and 3 years.

Although serous otitis media is painless, the fluid can impair hearing, understanding of speech, language development, learning, and behavior.

Doctors diagnose serous otitis media by looking for changes in the color and appearance of the eardrum and by squeezing air into the ear to see if the eardrum moves. If the eardrum does not move but there is no redness or bulging and the child has few symptoms, then serous otitis media is likely.

Serous otitis media often does not improve when treated with antibiotics or other drugs, such as decongestants, antihistamines, or nasal sprays. The condition often resolves by itself after weeks or months.

If the condition persists without improvement after 3 months, surgery may help. In the United States, doctors perform myringotomy, in which they make a tiny slit in the eardrum, remove the fluid, and insert a small ventilating (tympanostomy) tube in the slit to provide drainage from the middle to the outer ear. Some doctors may perform a myringotomy to remove fluid but not to insert ventilating tubes; this procedure is called tympanocentesis.

Malignant external otitis - from Merck Manual

Soft tissue, cartilage, and bone are all affected. The osteomyelitis spreads along the base of the skull and may cross the midline.

Malignant external otitis occurs mainly in elderly patients with diabetes or in immunocompromised patients and is often initiated by Pseudomonas external otitis. It is characterized by persistent and severe earache, foul-smelling purulent otorrhea, and granulation tissue in the ear canal (usually at the junction of the bony and cartilaginous portions of the canal). Varying degrees of conductive hearing loss may occur. In severe cases, facial nerve paralysis may ensue.

Diagnosis is based on a CT scan of the temporal bone, which may show increased radiodensity in the air-cell system and middle ear radiolucency (demineralization) in some areas. Cultures are done, and the ear canal is biopsied to differentiate the granulation tissue of this disorder from a malignant tumor.

Treatment is with a 6-wk IV course of a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside-semisynthetic penicillin combination. Extensive bone disease may require more prolonged antibiotic therapy. Careful control of diabetes is essential. Surgery usually is not necessary.

Monday, January 12, 2009

Epiglottitis - from Merck Manual

Symptoms

The infection usually begins suddenly and progresses rapidly. A previously healthy child develops a sore throat, and often a high fever. The child may be irritable and anxious. Difficulties in swallowing and breathing are common. The child usually drools, breathes rapidly, and makes a loud noise while inhaling (called stridor). The difficulty in breathing often causes the child to lean forward while stretching the neck backward to try to increase the amount of air reaching the lungs. Labored breathing may lead to a buildup of carbon dioxide and low oxygen levels in the bloodstream, causing agitation and confusion followed by sluggishness (lethargy). The swollen epiglottis makes coughing up mucus difficult. Epiglottitis can quickly become fatal because swelling of the infected tissue may block the airway and cut off breathing.

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Prevention of epiglottitis is better than treatment. Prevention is achieved by ensuring that all children receive the Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae conjugate vaccines.

Epiglottitis is an emergency, and a child is hospitalized immediately when a doctor suspects it. If the child does not have all of the typical symptoms of epiglottitis and does not appear seriously ill, the doctor sometimes takes an x-ray of the neck, which can show an enlarged epiglottis. The doctor does not hold the child down or use a tongue depressor to look in the throat. These manipulations may cause throat spasm and complete airway blockage in a child with epiglottitis.

If an enlarged epiglottis is seen on x-ray or the child appears seriously ill, doctors examine the child under anesthesia in the operating room. The doctor inserts a thin flexible tube (laryngoscope) into the throat to directly view the larynx. If the examination shows epiglottitis or triggers throat spasm, the doctor inserts a plastic tube (endotracheal tube) into the airway to keep it open. If the airway is too swollen to allow placement of an endotracheal tube, the doctor cuts an opening through the front of the neck (tracheostomy) and inserts the tube. This tube is left in place for several days until the swelling of the epiglottis goes down. The child also receives antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone or ampicillin -sulbactam. Once the child's airway is opened, the prognosis is good.

Laryngitis - from Wikipedai

Laryngitis, hoarseness or breathiness that lasts for more than two weeks may signal a voice disorder and should be followed up with a voice pathologist.

If laryngitis is due to gastroesophageal reflux:

- The patient may be instructed to take a medication such as Zantac or Prilosec for a period of 4-6 weeks.

If laryngitis is due to a bacterial or fungal infection:

- The patient may be prescribed a course of antibiotics or anti-fungal medication.

If persistent hoarseness or loss of voice (sometimes called "laryngitis") is a result of vocal cord nodules:

- Physicians may recommend a course of treatment that may include a surgical procedure and/or speech therapy.

Tonsillitis - from Wikipedia

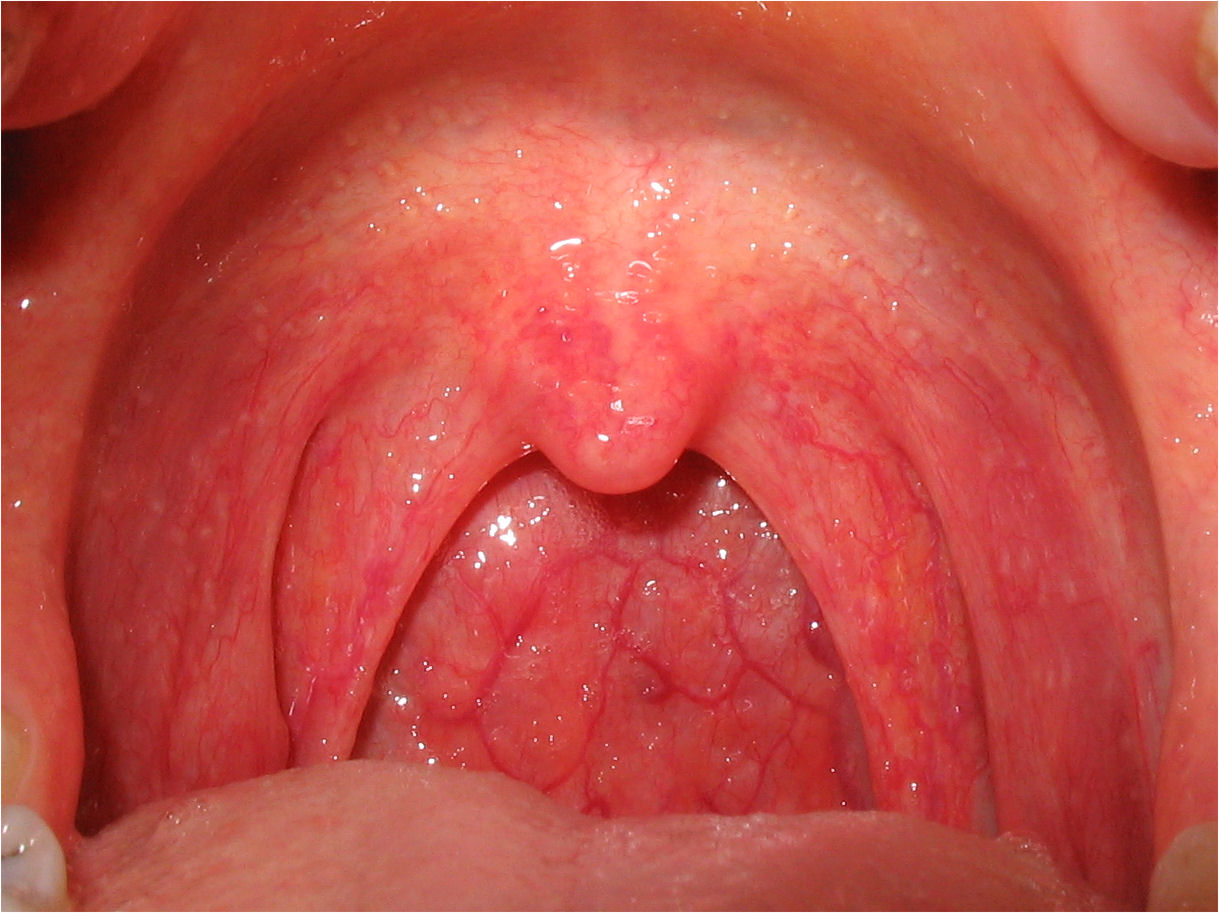

Symptoms of tonsillitis include a severe sore throat (which may be experienced as referred pain to the ears), painful/difficult swallowing, crouch coughing, headache, fever and chills. Tonsillitis is characterized by signs of red, swollen tonsils which may have a purulent exudative coating of white patches (i.e. pus). There may be enlarged and tender neck cervical lymph nodes.

Treatments of tonsillitis consist of pain management medications[4] and lozenges.[5] If the tonsillitis is caused by bacteria, then antibiotics are prescribed, with penicillin being most commonly used.[6] Erythromycin is used for patients allergic to penicillin.

In many cases of tonsillitis, the pain caused by the inflamed tonsils warrants the prescription of topical anesthetics for temporary relief. Viscous lidocaine solutions are often prescribed for this purpose.

Ibuprofen or other analgesics can help to decrease the edema and inflammation, which will ease the pain and allow the patient to swallow liquids sooner.[4]

When tonsillitis is caused by a virus, the length of illness depends on which virus is involved. Usually, a complete recovery is made within one week; however, some rare infections may last for up to two weeks.

Chronic cases may indicate tonsillectomy (surgical removal of tonsils) as a choice for treatment[7]

Additionally, gargling with a solution of warm water and salt may reduce pain and swelling.[8]

Retropharyngeal Abscess

- Physical signs in adults

- Posterior pharyngeal edema (37%)

- Nuchal rigidity

- Cervical adenopathy

- Fever

- Drooling

- Stridor

- Physical signs in infants and children

- Cervical adenopathy (83%)

- Retropharyngeal bulge (43%; do not palpate in children)

- Fever (86%)

- Stridor (3%)

- Torticollis (18%)

- Neck stiffness (59%)

- Drooling (22%)

- Agitation (43%)

- Neck mass (91%)

- Lethargy (42%)

- Respiratory distress (4%)

- Associated signs including tonsillitis, peritonsillitis, pharyngitis, and otitis media

A doctor suspects the disorder in children who have a severe, unexplained sore throat, a stiff neck, and noisy breathing. X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans of the neck can confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment and Prognosis

Retropharyngeal abscesses often need to be drained surgically. A doctor cuts the abscess open allowing the pus to drain out. Penicillin plus metronidazole, clindamycin , ampicillin -sulbactam, cefoxitin , or other antibiotics are given, at first intravenously, and then by mouth. Most children do well with prompt treatment.

Peritonsillar abscess - From Wikipedia

Progressively worsening unilateral sore throat and pain during swallowing usually are the earliest symptoms. As the abscess develops, persistent pain in the peritonsillar area, fever, malaise, headache and a distortion of vowels informally known as "hot potato voice" may appear. Neck pain associated with tender, swollen lymph nodes, referred ear pain and halitosis are also common. Whilst these signs may be present in tonsillitis itself, a PTA should be specifically considered if there is limited ability to open the mouth (trismus).

Physical signs include redness and edema in the tonsillar area of the affected side and swelling of the jugulodigastric lymph nodes. The uvula may be displaced towards the unaffected side. Odynophagia (pain during swallowing), and ipsilateral earache also can occur.

Treatment

Treatment is, as for all abscesses, through surgical incision and drainage of the pus, thereby relieving the pain of the pressed tissues. The drainage may be performed as an outpatient procedure, using a guarded No. 11 blade in an awake and co-operative patient. More commonly, a needle aspiration using a 9 or 10 gauge needle after a lidocaine and epinephrine gargle is used. Antibiotics are also given to treat the infection. Internationally, the infection is frequently penicillin resistant and for this reason it is now common to treat with clindamycin instead. Treatment can also be given while a patient is under anesthesia, but this is usually reserved for children or increasingly agitated or anxious patients.